Driving profit through heterosis – Opportunities with cross breeding

Across the Australian beef industry, the cost of producing a kilogram of beef varies considerably. Cost of production is an extremely useful tool for any beef enterprise. Producers who are willing to assess their cost of Production are well on the way to understanding what drive profit within their business and can more effectively address issues that are holding the business back from achieving a desired level of production and ultimately financial return.

For a beef business, operating margin is the difference between the average price per kilogram of beef sold and the cost of production per kilogram of beef. The 2023 Australian Beef Report, published by BushAgribusiness has analysed the statistics for northern & southern production systems. Considering average production systems over the past 12 years in northern Australia, the average price per kilogram received has been $2.82/kg while the Cost of Production (CoP) has been $2.35. The operating margin for northern systems over that 12-year period is $0.47/kg.

By way of contrast, the average southern beef production system for the same period received $2.90/kg sold, while CoP was recorded at $2.98. Meaning the average production system in southern NSW lost $0.08/kg.

While the variation between northern and southern production systems over the long term is significant, it is worth noting that these results are for an average production system. A closer look at the data, particularly for those in the top 25% for both regions shows greater degrees of variation again. In the north the Top 25% of producers long term performance showed their average price received was $2.72/ kg. Surprisingly this is some $0.10/kg lower than that received by the average producer. However, their CoP was also much lower at $1.59, resulting in an operating margin of $1.13/kg.

In Southern systems a similar trend is observable. The Top 25% of producers received an average $2.86 (some $0.04/kg less than the average) while their CoP was lower at $2.02. The operating margin for these businesses was $0.84/kg.

Taking the time to understand the financial position of a business is invaluable before embarking on a program of significant change to a herd or business structure. Production of beef per hectare is actually one of the greatest influences on cost of production and should be one of the key focus points for most producers.

While there are many ways producers can increase their production of beef per hectare, focussing on fertility should be a priority in any system. Fundamentally producers should be focussed on running a breeding herd where all breeding females are capable of conceiving and delivering a calf within a twelve-month period and then raising that calf to weaning while successfully re-joining.

This is an achievable goal for beef producers. However, it does require some focussed management ad careful attention to nutrition as well as a focus on selection and the genetic traits that impact on fertility.

It is possible to select genetics for increased fertility within herds. However, many of the traits associated with fertility tend to be of lower heritability, meaning the environment an animal lives in has much higher influence on how this trait may be expressed. Selection within breed can take a number of generations to significantly change the performance of a herd for traits with low heritability.

Cross breeding offers producers an opportunity to increase the rate of improvement in many traits. The impact of heterosis can be very significant in production traits such as growth or weaning weight. However, the greatest impact is often seen in traits that have lower heritability. As a result, cross breeding can have a significant impact on improving this aspect of a herd’s overall performance and can measurably contribute to improved fertility and ultimately increased kilograms of beef produced per hectare each year.

For many producers, cross breeding is not a new concept. However, there can be a reluctance for producers to consider implementing a system in their own business due to perceptions about difficulties in managing a program. These perceptions may include access to replacements, market considerations or loss of adaptability to an environment. To some degree these perceptions are often the result of poorly planned or poorly managed systems. Well-designed cross breeding programs offer significant production improvements. As long as a plan has been clearly defined and well followed the advantages generally surpass any associated challenges that may arise.

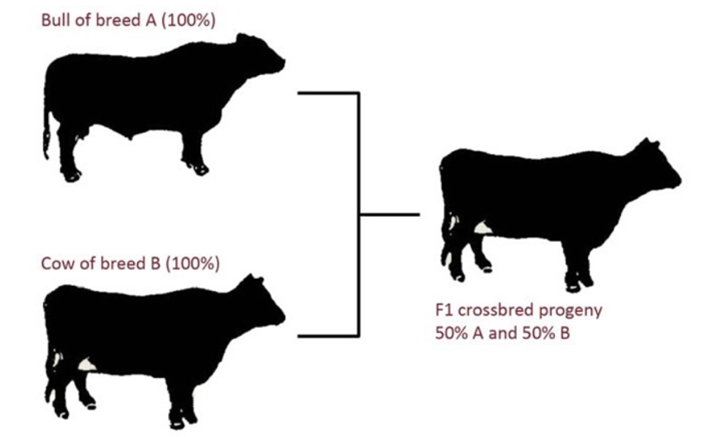

Two very effective cross breeding systems are the Two Breed Cross and the Rotational Cross. The two-breed cross is the most common system for many people. It simply involves using a bull from a different breed over the existing cow breed in a herd.

The progeny – known as F1 will display greater levels of production when compared to their straightbred siblings.

This system often results in increases in weaning weight increases of up to 5 -7% compared to the performance of strightbred cattle used in the program.

This system of cross breeding is extremely useful for situations where the cow herd may be well adapted to a given environment. Many producers with Bos indicus bred females in north, central and coastal Queensland use this method to specifically improve traits such as growth, improved carcase, feed conversion efficiency and vigour trough selecting a sire from a breed with these traits.

The use of Red Angus genetics is increasing in many areas as northern producers seek to improve these traits while retaining a red coat as part of their adaptation to heat. The impact of coat colour and an animal’s ability to cope with high temperatures has been well researched. Darker coated cattle are less heat tolerant, and as a result consume less and grow more slowly than lighter coated cattle. The impact of the heat can actually outweigh any advantages that may be gained from a cross breeding program. The choice of a sire is therefore of particular importance in order to ensure these gains are not lost.

One of the limitations of an F1 crossbreeding system is sourcing replacement females. There is generally a strong demand for F1 females which can be an attractive option for producers, but there can be a reluctance to purchase or to actually source suitable replacement females. In this case it is possible to consider undertaking a rotational or Criss Cross system.

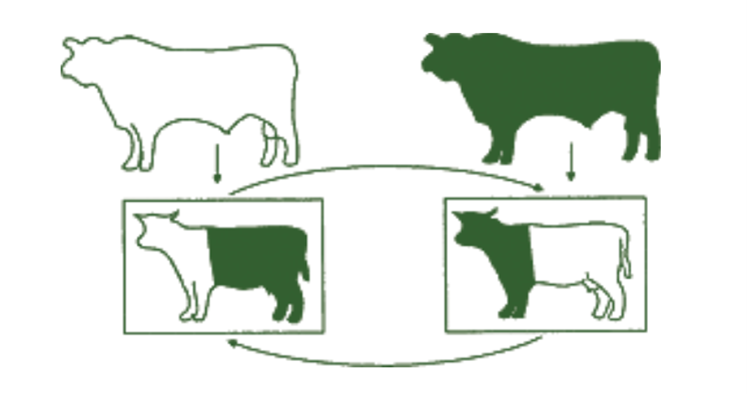

In this system a breeding herd can be divided into two groups. One group is joined to sires of the original breed, while the second are joined to a new breed.

In the following year those bulls are swapped over to join with the alternative breeding group. Replacement heifers are selected from either group. For maximum impact, at least one of the breeds should have strong maternal traits. These systems can result in production increases of 10 – 20% weaning weights compared to straightbred cattle.

It is important that producers don’t focus solely upon the increases that are possible. The most successful programs are those which firstly follow a clear program. Equally significant is the need to focus on the choice of breeds and selection of sires within a breed. It is true that choosing sires with average performance data (or no data) will still result in heterosis and improved performance in the progeny. However, average cattle will result in only slightly better than average production.

Longer term choosing to select cattle with better than bred average performance data will improve the overall outcome as well as increasing the overall rate of genetic improvement in a herd. The Red Angus data that now includes a Northern Steer Index (NTH) is a very useful tool for producers who are both seeking a sire to use in northern programs as well as for breeders looking to provide bulls into this region.

The Northern Steer Index considers the use of Brahman cows as a base, with the heifers being retained for breeding. This is effectively describing the commencement of a rotational crossbreeding program. Ideally producers who are attempting to meet a northern demand for cattle that improve production and eating quality should pay close attention to this index ad to the individual traits that contribute to how it is derived.

A well-designed cross breeding program, that uses above average and well described genetics generally captures improvements not only in increased weaning weights. Traits such as birth weight and gestation length do have an impact on calving rates and ultimately on kilograms of beef produced per hectare. In addition to these advantages, many producers who have struggled to achieve critical mating weights for heifers or to retain body condition scores on lactating cows have observed the superior performance of cross bred cows in these traits to straight bred females. These are important considerations for producers aiming to achieve a 12-month calving interval.

As beef producers seek to find effective and efficient methods to reduce their Cost of Production and increase their operating margins, the opportunities for cattle with accurate and reliable performance data will only increase. Producers will seek to use these cattle not only in strightbred programs, but increasingly in crossbreeding systems for the advantages outlined previously. Longer term the increased variation in weather events, particularly the number of extreme heat events will also influence many producers’ decisions on sires and breeds. Its highly likely that breeders who can offer cattle that can at the very least tolerate heat events combined with well described genetics will find their cattle in increased demand.

– Alistair Rayner

Principal RaynerAg